Randomness is a topic that comes up quite often in game design and development. It is also a difficult topic to comprehend for some. Without it you may end up with a very linear game that offers little replay value.

When it comes to computers there is no such thing as "true random". Technically any computer-based random number generator (RNG) is built around some type of pseudorandom number generator (pRNG). While the mechanics of how computers generate random numbers isn't the subject of this post, Wikipedia has some great information on that topic. In game development it is pretty much understood that the pRNG system is more than good enough to serve our needs – otherwise we would need someone in the background rolling a lot of dice to get a true RNG for every action in a game.

Games generally use random numbers for things such as character stats, attack damages, loot rewards, generating maps, and the like. Most of these examples fall within specified ranges to offer a balanced, or at least structured, design.

By assigning random stats at character creation you can force a player to adapt to their stats or to find a different play style. This is common in class-based characters such as you would see in the pen and paper game Dungeons & Dragons. If you choose a melee type class but your strength is quite low, your attacks will be underpowered and this can lead to more difficult gameplay in the beginning. Whereas if your strength is much higher than normal you will likely start off at an advantage.

Combat in turn based games requires knowing which character attacks next. Using a stat such as "SPEED" is great for this. If you control a team of characters and you can manipulate your speed stat then you can pre-determine which order your team will go in (barring any outside influence). As far as the enemies go, randomizing their speed stat will affect the full order of turns.

Probably the most controversial use of RNGs in games though is for rewarding loot. This is especially true in games that have tiered classifications of items such as "World of Warcraft": (e.g., "JUNK", "COMMON", "UNCOMMON", "RARE", "EPIC", "LEGENDARY"). What this means is that if you defeat an enemy, there may be two (or more) pools of prizes from which your reward may be pulled. Most games that use such a ranked system (e.g., World of Warcraft, Borderlands, Monster Hunter, Overwatch) also utilize prize pools.

In terms of game design, you will assign each pool a chance rating. It wouldn't make sense for every enemy kill to have the same chance of dropping a "Common Wand" and the "Legendary Wand of Flamestrike". Otherwise your players will end up with all of the unique items and gear before they even have a chance to really play the game. Don't do that. Unless that's the type of game you're trying to make.

Balance is an integral part of any game. Use your RNGs wisely. You can think of your prize pools this way:

- JUNK & COMMON – 90%

- UNCOMMON – 6.0%

- RARE – 3.5%

- EPIC – 0.4%

- LEGENDARY – 0.1%

There is a 90% chance of pulling a reward from the first pool. This means that every time it rolls for your prize, there is a 90 out of 100 chance of coming from that pool. It also means there is a 1 out of 1000 chance of a prize from the LEGENDARY pool. What this doesn't mean is that if you roll 1000 times you will be guaranteed an item from the LEGENDARY pool. If you flip a coin 100 times, it is always a 50% probability of being heads. You would expect to get roughly 50 heads and 50 tails, but you could still end up with tails 99 times. That's called random chance and there are plenty of articles and videos describing the difference between chance and probability.

Hopefully that gives you a little more insight into how "randomness" is used in game design.

Occasionally I have the urge to stream on Twitch – whether it's development work, or just playing around in Photoshop. At the same time, I also want my audience to have fun and be captivated by more than just what I'm doing.

That's why over the weekend I decided to build a Twitch minigame using JavaScript. And to make it extra meta, I built a lot of it live during a stream – with input from the audience of course.

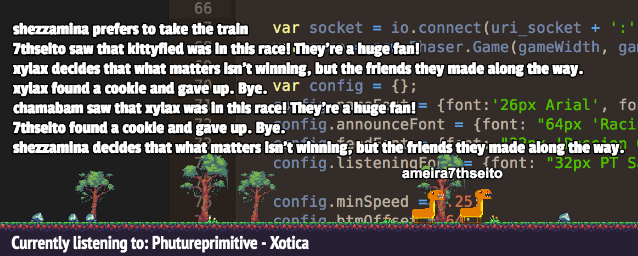

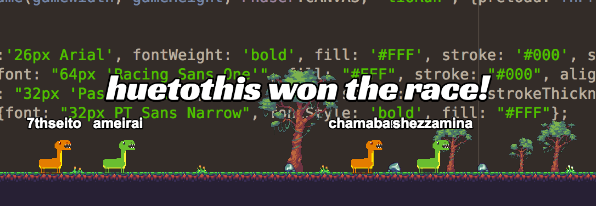

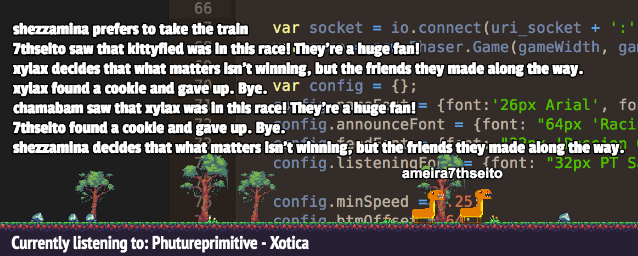

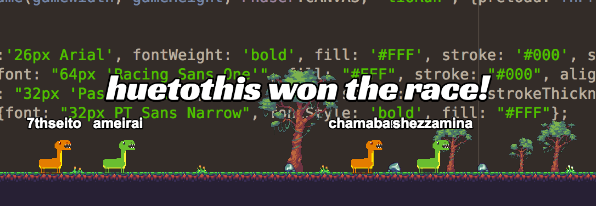

The gist of it is that the audience can join in the race (by writing "!join" in the chat, or whispering it to my game bot). Each round, the players are populated onto the field which is overlayed on whatever I'm working on. Then the race begins. Players' speed fluctuates randomly in small amounts and at random intervals.

There are also random events that can increase or decrease a players speed (or in some cases, cause them to start leaving the field).

Each time someone wins, they earn some points. My eventual goal is to add new skins/creatures that people can spend points on to unlock. Just cosmetic changes, though. I still want the speeds and whatnot to be random.

On the technical side of things, here's what's going on in the background:

First, there is a bot running via node.js that connects to the Twitch IRC channel of my stream. It monitors the chat for incoming commands (both in public chat as well as whispers to my bot account). This is done with help from the Twitch Messaging[1] library. The second half of the equation is the "client"; this is simply a single page served locally that displays the game view and communicates over sockets[3] with the bot script. The view is written using PhaserJS[4] to handle the graphics rendering.

When a player joins the race they are added to the queue which is stored in Redis[2]. This is similar to a player sending the "!points" or "!stats" commands; the information is queried from Redis and then returned via Twitch Messaging.

if (message === '!stats') {

getPlayerData(uID, function(pData) {

client.whisper(from, 'You have won ' + pData.wins + ' time' + ((pData.wins) !== 1 ? 's' : ''));

}, this);

return;

}

Once the race finally begins the bot uses a socket connection to populate the field in the game view. Since the display is only rendered in the stream and is not directly accessible by the audience the socket calls are not authenticated. When a player hits the chest at the end of the race it triggers the "game over" condition and fires a message back to the bot. It's at this point that the number of wins and points are updated in Redis.

One final piece to the overlay is the "Currently listening" to bit. I modified the Scroblr[5] extension to send the current track information to my bot script. Captured as an HTTP request, the data is then stored in Redis and also sent via socket to the game view.

var data = require('querystring').parse(request.url);

var currentSong = {

"artist": data.artist,

"track": data.track

};

rdb.set('currentSong', JSON.stringify(currentSong));

io.sockets.emit('listeningTo', currentSong);

Resources:

[1] Twitch Messaging (node module)

[2] Redis (node module)

[3] socket.io (node module)

[4] Phaser JS

[5] Scroblr browser extension

[6] Pixel art courtesy KnoblePersona

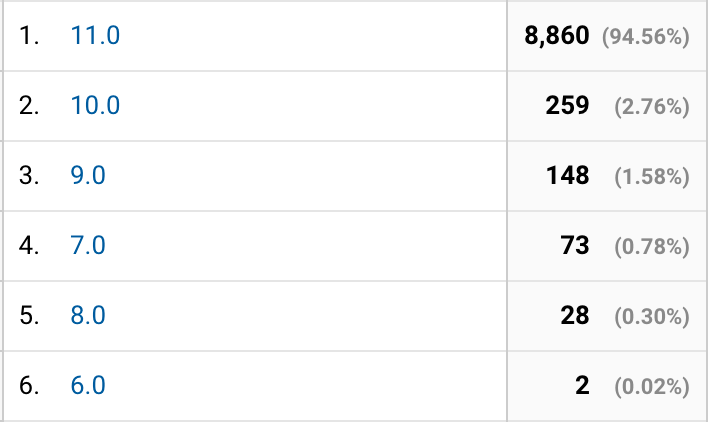

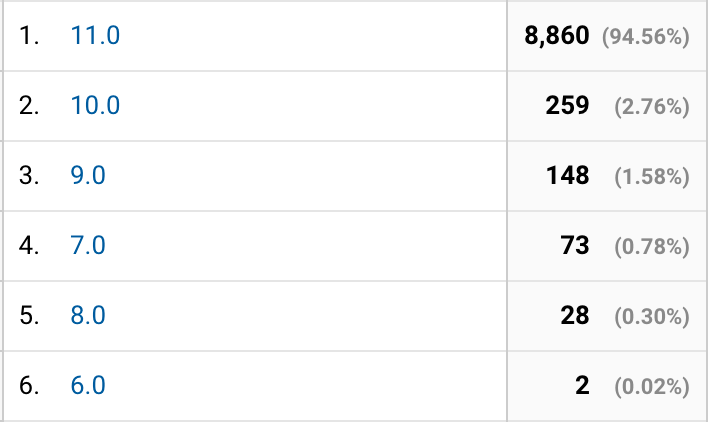

In the years that I have been developing websites and browser games, one major roadblock has always been browser usage. Trying to accommodate users who are unable to switch to a more modern browser, or not technically inclined to do so, certainly proves challenging when you want to take advantage of exciting new technologies.

I was curious to see what our numbers looked like after reading that Bootstrap would be dropping support for IE9. While I don't personally utilize Bootstrap for any of my projects, I find that it is a decent benchmark when widely adopted projects start dropping support for archaic platforms.

For that reason it is refreshing to see the percentage of people using modern browsers on our sites at an all-time high.

With Internet Explorer at only 2.12% usage, it is even more reassuring to look deeper and find that 94.56% of those users are at least on the most recent version.

I have to imagine that the two sessions in IE6 were some type of testing suite. Right?

I don't work on AAA games. I don't even really work on what you would consider "traditional games". Instead, my background in game development is mostly centered around website-based games (like Neopets™, but not). Over the years I've contemplated blogging about my experiences, ideas, discoveries, as well as my mishaps and misfortunes. Perhaps it would help some, make some laugh, and possibly inspire others.

My first experiences with any sort of game development were with Play-by-Post roleplaying games. Utilizing a community platform known as "Comfusion" I was able to bring interactive storytelling to life. The more I became involved with general web development, the more I realized the potential for creating new types of imaginative and interactive content.

As time went on I would become more involved with "pet games"— the kind where people collect specific types of creatures to raise, train, and dress them up. I started out by creating mini-games within these games, whereby players could earn in-game currency, items, and other rewards. Ultimately this would lead to working on projects of a much larger scope. Projects where I could utilize the full extent of my knowledge gained from building regular web sites: interface design, database management, server-side software configuration, all the way up to server deployment. As new technologies emerged I would find ways to incorporate them: full-text search systems, graph databases, Redis, sockets, you name it. If it could be used in a web site it could be used in a game.

These days I spend much of my time working on a project titled "Evosaur"—a game focused on collecting and raising dinosaurs (you can see it on my screen in the image above)– as well as continuing to tinker with new ideas, technologies, and challenges. Through this blog I would like to share what I do with fellow and aspiring game developers, people who just love to play games, and even web developers or those that like to build and learn new things. I plan to share things like tips & tricks, problem solutions, code snippets, and playable prototypes.

Who knows, maybe you'll learn something new!